English is a funny language!

Manoj KC

EEE

1989

Many of us may remember a hilarious dialogue by Amitabh Bachan from 1982 movie, Namak Halal, where he says “English is a funny language” and goes on to describe a number of examples. Well, it may indeed be a funny language, but by far the most popular one, if one goes by the number of people speaking English. Mandarin may be at a close second but considering the dominance of the western world in the field of technology, trade and wealth, Mandarin may not be able to get ahead of English in the foreseeable future.

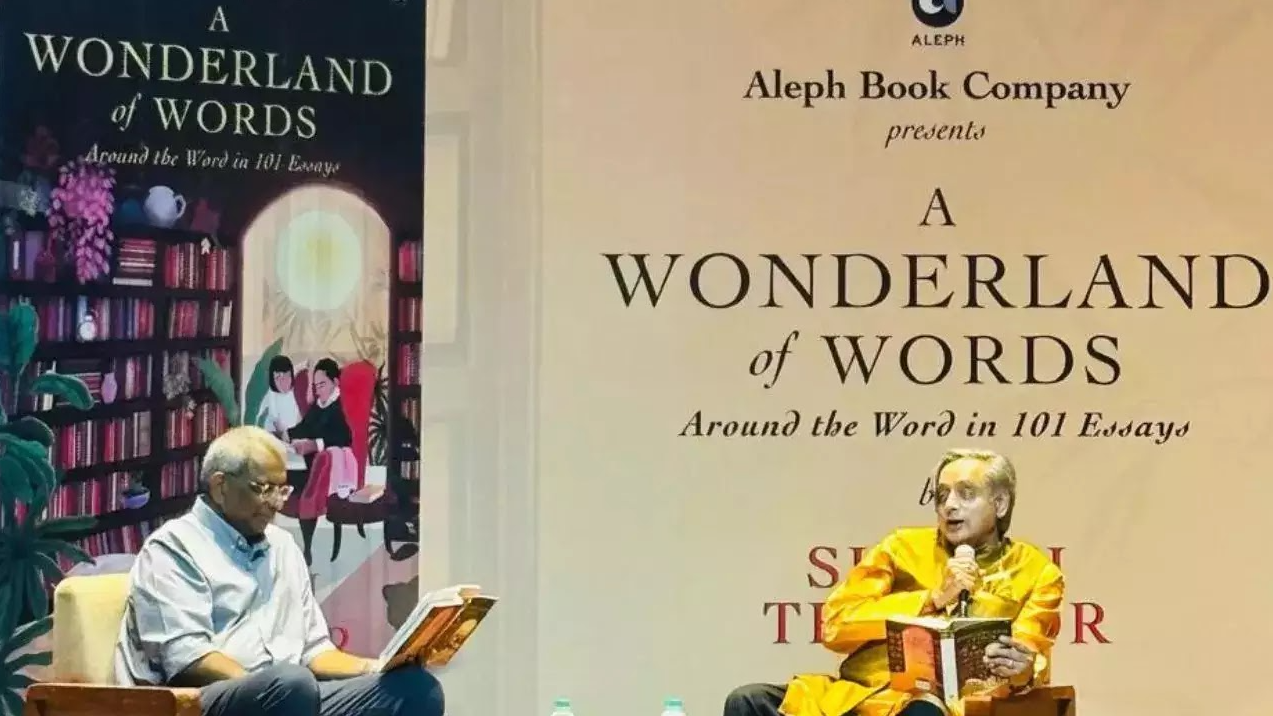

“A wonderland of words” written by Shashi Tharoor takes us through the nuances and quirks of this funny but wonderful language. Shashi’s outburst “farrago of distortions, misrepresentations and outright lies broadcast by an unprincipled showman masquerading as a journalist”, against a libellous TV program marked him out for his tough vocabulary and what then followed were a barrage of memes and parodies. Tharoor too enjoyed this spotlight and occasionally dropped what was till then an unknown word to draw attention. Thus, floccinaucinihilipilification was mainstreamed during the launch of his book on Prime Minister Mr. Narendra Modi titled “The Paradoxical Prime Minister”.

With 13 sections and 101 essays, the book is easy and fun to read. It takes us through interesting words, phrases and their etymology using humorous anecdotes and few history lessons.

The first section is about words that are not English but have become part of English vocabulary and about the variants of English used in different countries. He highlights the differences between British and American English using some hilarious examples. To state a few here – “A ‘moot’ point is one which the Englishman wants to argue, but if its ‘moot’, the American considers it null and void. The British ‘stands’ for elections whereas the American ‘runs’ for the office.

English is popular in most of the erstwhile British colonies and there are local adaptations of how the same word is pronounced. This example illustrates it well – A tourist who meets with an accident in Australia wakes up from coma and asks the nurse, ‘Have I come here to die? The nurse cheerfully replies, ‘No, you came here yester-die.’ Schadenfreude, a word borrowed from German was popularised to criticise the media attack on Shah Rukh Khan’s son. The words used by Shashi to decry the act was ‘ghoulish epicaricacy’, which sounds even more Latin!

There are a host of Indian usages that are very practical but may not be understood when used in America or Britain. Examples are calling elders ‘uncle’ or ‘aunty’, ‘non-veg’ to convey that you eat fish and meat, ‘air dash’, ‘history sheeter’ or if you say you were ‘mugging’ for an exam. Our matrimony columns have another set of vocabulary like ‘wheatish complexion’, ‘homely’, ‘convent educated’ to state a few. While most of these are useful and practical, there are others that are wrong, but used regularly, like, ‘return back’, ‘entry through back side only’, ‘years back’. The worst I have come across is people asking, how many ‘issues’ you have, to mean children.

The section 2 is about punctuations. We are familiar with how the meanings change with a wrong placement or usage of punctuations. An example to illustrate the point; A computer teacher announced to the class; ‘today let us learn how to cut and paste kids’.

Anyone using English would have faced issues with spellings and its absurdities. Section 3 deals with these. With same combination of letters pronounced differently and having different meaning, it is a nightmare to correctly spell what we want to convey. What more can one say when ‘sew’ and ‘new’ do not rhyme but ‘kernel’ and ‘colonel’ do and there are six different ways to pronounce ‘ough’ (Cough, tough, bough, through, thought, though). Apparently, 60 percent of English words have silent letters. They can be anywhere in the word and follows no obvious rules!

Have you ever thought why we say tick-tock, ding-dong, singsong, criss-cross, wishy-washy, hip-hop etc and not the other way round like dong-ding, cross-criss etc? Well, these follow the rule of Ablautreduplication. Yes, that is what it is!

How many times have we laughed at misprints or got frustrated with superfluous sentences? I am sure most of us have wondered why the legal language is so weird, with extremely long sentences and superfluities. In section 4, there are plenty of examples, that draws a good laugh and make us careful when we frame sentences. Then there are examples of pleonasms to be avoided.

Section 5 familiarises us with words and phrases borrowed from various professions, starting with diplomatic-speak, which the author should be at home with considering his long stint with the UN. In his own words, diplomats think twice before saying anything and if they indeed must, use the most measured and polite words even to convey the harshest things. Interesting examples are ‘candid exchange of ideas’ instead of ‘heated arguments’ or ‘deeply concerned’ instead of ‘will not do anything’.

There are many chapters in this section that deals with words that originated from different professions. Here are a few interesting words from maritime, aviation and warzone. ‘Blackout’, ‘blitzkrieg’, ‘skelter’ and ‘chatterbug’ are from the warzone. ‘Fathom’, ‘pipe down’, spinning yarn’ and ‘swallow the anchor’ are Nautical jargons. ‘Mayday’, ‘ahead of the curve’, ‘pushing the envelope’, ‘taking a lot of flak’ and ‘pressing the panic button’ from the aviation field.

Section 6 is on inappropriate words. Words could be inappropriate because they are used in a wrong context or place. And there are the most appropriate words that are hardly used. I have used a few such words to frame a sentence. During one of my mundivagant tours of France, I ran in to a friend who invited me home. However, I considered it apposite to accismus, only to be taken literally by my friend. This akratic conduct of mine resulted in infelicifix. Shashi Tharoor feels these words are very precise and it is a pity that we do not use such words frequently!

Section 7 is about various tools used in the language like alliterations, anagrams, aptagrams, anaphora, acronyms, bacronyms, contronyms, eponyms, homonyms, oxymorons and antonyms. Few of these may not be familiar to us. So, check those out to improve your English.

Sections 8 describes literary acrobatics. Sometimes words are misheard and then becomes a normal usage. For example, expresso for espresso. Hilarious mistakes are called malapropism named after Mrs. Malaprop, a fictional character, invented by playwright Brinsley Sheridian in 1775. Someone said, ‘having one wife is called monotony’ when he meant ‘monogamy’!

Paraprosdokians will have an interesting twist at the end of the sentence. Consider this – ‘the last thing I want to do is to hurt you, but it is still on the list.’ Or ‘if at first you don’t succeed, skydiving is not for you’. You can be a connoisseur of dry humour with a stock of paraprosdokians in your custody.

We are familiar with puns, hyperbole and red herrings. Aspiring politicians should attain expertise in these techniques to be successful. However, to try stand-up comedy, practice spoonerism, named after an absent-minded Reverend, Spooner, who was famous for switching vowels and consonants. Examples are ‘blushing crows’ for ‘crushing blows’ or asking, ‘is the bean dizzy’ instead of ‘is the Dean busy’? Does this ring a bell? In Malayalam, we have something similar and is used in a naughty way!

Quirks in English language are dealt with in section 9 deals. While a vegetarian eats vegetable, a humanitarian does not eat humans. We put cups in a dishwasher and dishes in the cupboard. We also have ‘smelly feet’ and ‘running nose’. Money does not grow on trees, but banks have branches. Worst of all… word ‘funeral’ start with the word ‘fun’! Then there are kangaroo words, where the word contains all the letters of its synonym. Example ‘masculine’ contain ‘male.’

Using metaphors is a good way of getting one’s point across. However, if one mixes incompatible metaphors, the outcome could be funny to say the least. Consider this; ‘we will burn the bridge when we come to it’. Having said that, Shakespeare was well known for mixed metaphors. And (maybe) because he is Shakespeare, these became famous! If lesser mortals like us use it, we would be laughed at.

Section 10 is about how different words evolved. Food preferences from an uncomplicated vegetarian / non vegetarian has added many shades like vegan, lacto-ovo vegetarians, pescatarians etc. Even country names have evolved. In our country, it is almost an epidemic with new names for cities, towns, roads and even public utilities like Airports and Railway stations. Many words are invented when a need arises because there isn’t an appropriate word to describe it. Tharoor himself came up with a new word ‘algospeak’ to mean words that will not be blocked by algorithms in the age of social media. Finally, the section talks about the various trademarks that became part of the language – Google, Xerox, Bandage, Polaroids and Velcro to name a few.

Social systems and hierarchies change over time mostly for the good. There might be short term setbacks, but considering the trajectory over multiple generations, the changes are progressive. We have evolved from a society that considered child labour and slavery as legitimate to one that considers it to be a crime. Children were seen to be the most suitable for professions like chimney cleaning as described in Oliver Twist and many other works of Charles Dickens. Even Immanuel Kant who theorised and wrote about enlightenment was ambivalent about slavery. Ancient Greece did not consider Women to be eligible for citizenship. We have travelled a long distance from there. It is only recently that there is a realisation (and acceptance) about gender binaries being a myth and societies started decriminalising gay relationships. While the rule of law can ensure punishment for the delinquent, it is only through conscious social transformation that such changes can be made universal. Language plays a major role in bringing about such change. Many words that were normal are now a taboo. A majority still scoffs at being politically correct and avoiding such taboo words or inappropriate jokes. However, I make a conscious attempt to encourage this change in my interactions. Section 11 has multiple chapters that talk about this transformation in the language and covers euphemisms, language of equity, Stanford Universities initiative to eliminate harmful language, Oxfam’s language rules and sexist language. Oxfam suggests using ‘AFAB’ (assigned female at birth) and ‘AMAB’ (assigned male at birth) instead of ‘female’ and ‘male’. Maybe an extreme example, but who knows, this may get mainstreamed, and ‘M’ and ‘F’ may become offensive shortly.

The last two sections too take us through many more words that became popular due to iconic works like Adventures of Tintin and the humorous novels by P G Woodhouse. Evolving business and marketplace also have created its own share of popular words, which no more means what they originally meant. So, an investor may take a ‘haircut’ to minimise losses or may track a ‘bellwether’ company to plan his investments.

Each year new words are infused into the English language. Various organisations come up with their choice for being the “words of the year” and this has progressed from being a mere linguistic exercise to being a cultural barometer reflecting the preoccupations or ethos of the society at that time. For 2024, Oxford has chosen “brain rot” and with the popularity of reels and the mindless scrolling that the masses indulge in, brain rot remains my word of the year too.

English indeed is a funny and evolving language and through ‘A wonderland of words’ Shashi Tharoor provides an interesting and engaging tour.