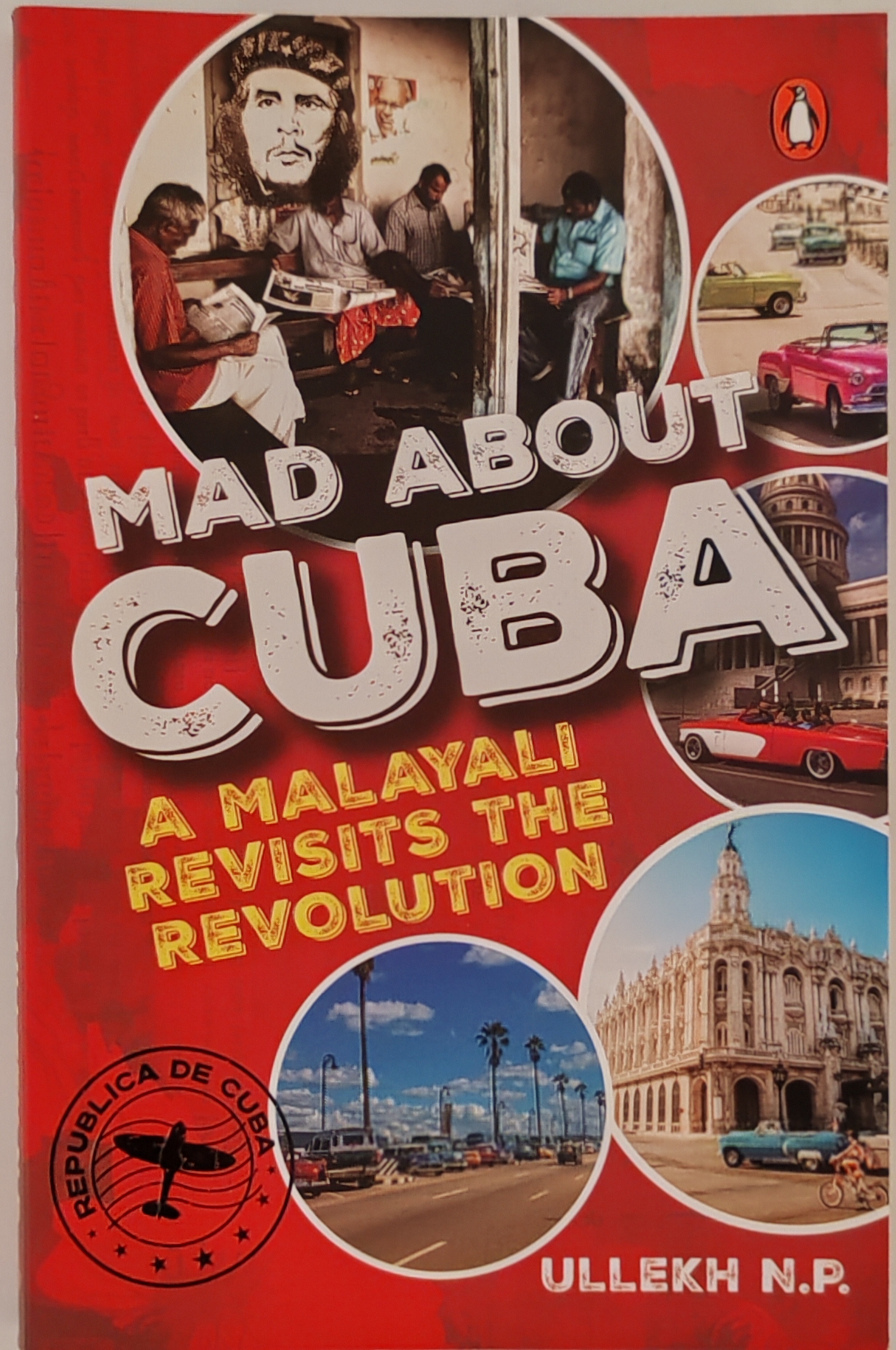

Mad About Cuba - Book Review

Santhosh Kumar K

CE

1988

‘Mad about Cuba’ by N.P. Ullekh is a deeply resonant and thought-provoking book, especially for a reader from Kerala. The parallels between Kerala and Cuba—ranging from political ideologies to cultural vibrancy—make this exploration of Cuba’s history, politics, and society particularly engaging. Ullekh, a journalist with a keen eye for detail, weaves together a narrative that is both informative and evocative, offering insights that feel familiar yet profoundly enlightening. The book is a compelling blend of travelogue, political history, and cultural exploration, taking readers on a journey through Cuba’s revolutionary past, its socialist present, and the challenges it faces in a rapidly changing world. It delves into the lives of iconic figures like Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, examines the impact of the U.S. embargo, and celebrates Cuba’s rich cultural heritage, from its music and art to its resilient spirit.

Both Kerala and Cuba share a strong history of leftist movements. Kerala was the first place in the world to democratically elect a communist government in 1957, while Cuba’s revolution in 1959 established a socialist state. Malayalam cinema and literature have long been influenced by global socialist movements, and Cuba often features prominently in these narratives. For instance, the movie ‘Arabikkadha’ features a protagonist named Cuba Mukundan, symbolizing the deep connection Keralites feel with Cuba’s revolutionary spirit. The famous dialogue from the movie ‘Sandesham’, “Don’t speak a word about Poland,” humorously reflects how deeply the Malayalee psyche is influenced by international socialist experiments, including those in Cuba, the USSR, China, and Eastern Europe. In Aravindan’s ‘Oridath’, the discussions in local tea shops about the USSR and other socialist countries highlight how ordinary people in Kerala were engaged with global socialist movements. These references in Malayalam culture underscore the shared ideological and emotional ties between Kerala and Cuba, making Ullekh’s exploration of Cuba’s socialist journey particularly relatable.

Ullekh’s detailed account of Fidel Castro’s rise to power and his unwavering commitment to socialism reminded me of Kerala’s own communist experiments like land reforms and other social movements. Cuba’s achievements in education and healthcare under socialism are well-documented, and we can draw parallels to Kerala’s own success in these areas. Ullekh highlights how Cuba’s literacy rate soared to nearly 100% after the revolution, thanks to nationwide campaigns like the 1961 literacy drive. This reminded me of Kerala’s own emphasis on education, which has resulted in one of the highest literacy rates in India. The book also discusses Cuba’s universal healthcare system, which has produced impressive health indicators despite limited resources. This echoes Kerala’s own public health achievements, such as its high life expectancy and low infant mortality rates, achieved through a focus on primary healthcare and community participation.

Just as Kerala is known for its rich traditions in art, literature, and music, Cuba’s cultural landscape is equally vibrant. One particularly memorable passage describes the Afro-Cuban rhythms of Havana’s streets, where music and dance are integral to daily life. This resonated with me as a Keralite, as our own folk and traditional art forms.

There are many other such parallels between Kerala and Cuba, which are highlighted in the book. Ullekh describes how Cuban workers in cigar factories would have a designated reader who would read aloud from newspapers, books, or political pamphlets while they worked. This practice not only educated the workers but also kept them politically informed and engaged. This tradition finds a direct parallel in the beedi-making units of North Kerala, where workers would similarly listen to readings of newspapers, literature, and political texts. This shared practice reflects the deep-rooted culture of intellectual curiosity and political awareness among working-class communities in both regions. It also highlights how education and political consciousness were seen as tools of empowerment, transcending geographical and cultural boundaries.

The interactions Ullekh had with a section of Cuban people, reveal a growing sense of disillusionment especially among the younger generation, who did not directly experience the revolution but are now grappling with consequences of US embargo. This sentiment parallels the situation in the Soviet Union just before its collapse, as outlined in their book ‘Revolution from Above’ by David M. Kotz and Fred Weir. In both contexts, there is a profound resentment among the youth, who feel disconnected from the ideological fervor of the past and are more concerned with the present-day economic hardships and lack of opportunities. Ullekh’s portrayal of young Cubans, who are increasingly critical of the government’s inability to adapt to global changes and provide for their aspirations, mirrors the frustration felt by Soviet citizens in the late 1980s and highlights how the failure to address the evolving needs and expectations of the younger generation can lead to a crisis of legitimacy for socialist regimes, ultimately threatening their survival. This generational divide underscores the challenges of sustaining revolutionary ideals in the face of modern realities.

Ullekh’s writing is both informative and engaging. His ability to blend historical facts with personal anecdotes makes the book accessible to a wide audience. For example, his description of visiting Che Guevara’s mausoleum in Santa Clara was both poignant and insightful, offering a glimpse into the enduring legacy of the revolutionary icon. The book’s celebration of Cuban culture resonated with me, as it highlighted the importance of art and tradition in shaping a society’s identity—a value that is deeply ingrained in Kerala’s ethos. Ullekh’s account of the annual Havana Carnival, with its vibrant parades and music, brought to mind Kerala’s own temple festivals, where the entire community comes together to celebrate.

N.P. Ullekh’s personal accounts of tasting Cuban cigars and liquor add a delightful and intimate layer to the book, offering readers a sensory experience that goes beyond the political and historical narrative. He describes the ritual of smoking a Cuban cigar as almost ceremonial, with its rich aroma and slow burn symbolizing the island’s enduring spirit and craftsmanship. Ullekh’s vivid portrayal of savoring a Cohiba or Montecristo, often accompanied by the rhythmic beats of Afro-Cuban music, transports readers to the heart of Havana’s vibrant culture. Similarly, his experiences with Cuban rum, particularly the world-renowned Havana Club, are recounted with a mix of reverence and enjoyment. He writes about the smooth, caramel-like flavor of aged rum, often enjoyed in dimly lit bars where the walls seem to echo with stories of revolution and resilience. These personal anecdotes not only humanize the narrative but also serve as a reminder of how deeply intertwined Cuba’s cultural identity is with its everyday pleasures, making the book as much a celebration of life as it is a chronicle of history.

While the book offers a comprehensive overview of Cuba’s history, it falls short in providing a deeper analysis of the country’s current economic challenges and the effects of globalization. Perhaps this was not the author’s primary intent. For instance, he briefly mentions Cuba’s dual currency system and the growing inequality it has caused but does not explore these issues in depth. Some readers may find the portrayal of Cuba’s political system somewhat one-sided. Incorporating dissenting voices or critical perspectives would have added greater nuance to the narrative. Including accounts of Cubans who have experienced political repression or economic hardship alongside the discussions of Cuba’s socialist achievements, could have provided a more balanced perspective.

‘Mad about Cuba’ is a fascinating read, especially for someone from Kerala who shares a similar history of political idealism and cultural richness. N.P. Ullekh’s ability to capture the essence of Cuba its triumphs, struggles, and enduring spirit, makes this book a valuable read on global political and cultural studies. For Keralites, it offers a mirror to our own experiences and a reminder of the power of resilience and hope. I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in understanding Cuba’s unique journey or exploring the shared histories of seemingly disparate regions. It is a testament to the enduring power of ideology, culture and the human spirit.

****************************

ULLEKH N P

ULLEKH N P

Ullekh N.P. is a journalist and political commentator based in New Delhi. Hailing from Kannur, he is the son of the late Com. Pattiam Gopalan, a former Parliamentarian. With nearly two decades of experience in journalism, he has worked with some of India's leading news publications, including The Economic Times and India Today. Known for his in-depth analysis of domestic and international politics, he has reported extensively from across India and abroad.